I approach it gingerly as though I’m not looking, but I am. I always look. I have been looking at this place my entire life. I pull into the driveway and park beside a mini-skip. It is bashed in on one side where I imagine someone has backed into it. I hate the skip. It reminds me we are selling our family home, my sister and I. We are being practical, grownups, now our are parents are gone. It is up to us to be wise. You see, if we sell we will be more financially secure. If we don’t, we will need to spend a lot to keep the old place going, a great chunk of what we have. So, it’s sensible.

As I walk up the ramp and across the crazy slate tiles to the front door, there is a murmur coming from my heart. It is as if the place and heart are calling to each other. I key in the code to open the door on a panel attached where a lock once was. We had the panel installed when my parents became so security-conscious, Seal Team Six couldn’t penetrate. A code supplied to the local police, fire station and ambulance solved the problem of a potential rescue, not that it ever came to that.

I open the door and I walk across the flowered carpet, straight through, as I always do, to the side of the house which faces the river. It is the river, along with the house, which filled my childhood to the point that I, writer that I am, cannot imagine an alternative. The boats, the sand, Mum yelling at us because of the sand we accidentally brought into the house gave the floorboards a good scouring; hence the flowered carpet. Mum was sick of us not washing our feet at the tap outside. She had the carpet laid, not the flowered one in the beginning. It was a green shag pile first, I think and by the time that was too worn to be chic, it was so heavy with sand it had to be cut into small pieces to be removed. The flowered one came next.

I slide the heavy wood and glass door open. It catches now on its runners. I think it has something to do with the tracks it runs along and possibly the sand too. Just before I go out, I check the grandfather clock which stands against the wall beside the door. My ex-husband and I bought my father this clock for his seventieth birthday and he loved it. I knew things were getting too much for him when he reached ninety-five and Mum was gone, but I really knew it when he started to forget to wind the clock. That was when I got the nurses to come and check on him a couple of times a week.

I was regularly staying with him too, but he was a handful because he wouldn’t leave the house for a nursing home, not in a thousand years. He was also active for his age. Too active and ever so slightly awkward, from birth you understand. This was not an ageing thing. Mercurochrome was the thing he used, when he ‘barked’ his shin. He’d run after us with this weird two-tone red-green mix when we hurt ourselves and, if he caught us, whatever injury we had would look far more serious after he’d been dabbing at it. Still, when he got very old, his skin became thin and the ‘barking’ of the shin was more problematic. It was not unusual for me to open the door to find the kitchen like a crime scene after Dad knocked himself on the open door of the dishwasher. I would follow the bloodtrail and find him sitting up in bed reading the newspaper without a clue.

He took to a using a walking stick when he was ninety-five, a gnarled bit of wood my mother found on their travels out west and made him varnish. It looked like Gandalf’s staff. Wherever we went, people admired it and he would say different versions of, “My wife Maggie was a magpie. She couldn’t’ go past a thing we found in the bush, if she liked it enough.” It was true. Mum was of that era where you picked up the shells off the reefs up north, if you thought they might make a good lamp or ashtray (gasp) and where, if you liked the look of a plant in a garden or a national park (gasp, gasp), there was no harm in taking a cutting. I remember Mum on walks around the neighbourhood with her small garden shears in her back pocket. When a resort was built down the end of the road, Mum and my godmother would slip down, similarly armed, and strategically attack the many varieties of hibiscus.

I walk out onto the verandah. I am careful from habit, even though my reason for being so is long gone. One of Mum’s favourite pot plants, a big-leafed ornamental thing, used to stand in its pot by the door. “Be careful of the plant. Watch the plant,” she’d say, as we rushed past, and we would swivel our hips to avoid it. It occurs to me as I pass the phantom plant, this might be why both my sister and I are quick on our feet.

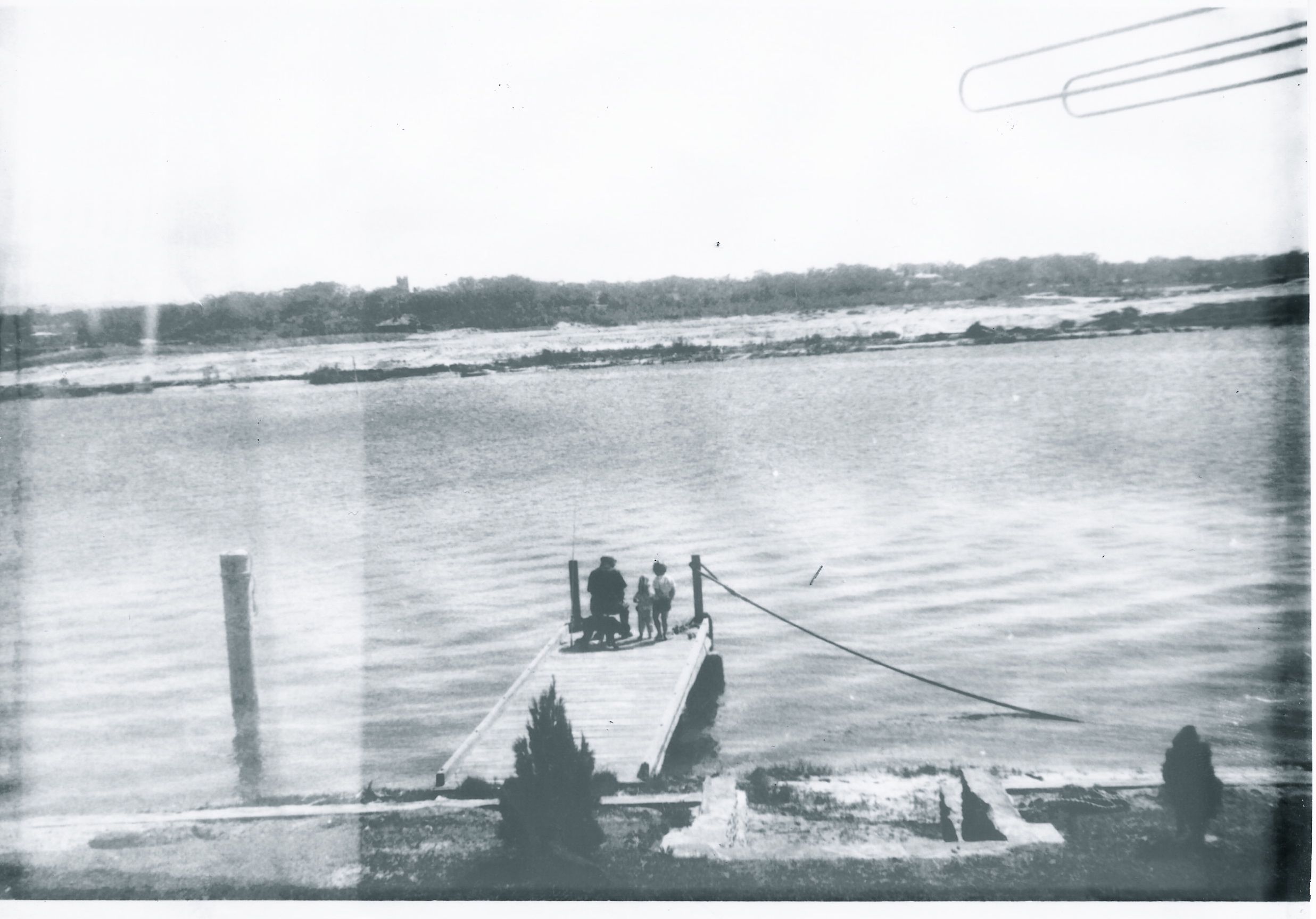

Now, I can see the river, with our jetty jutting into it. It’s not one of those floating pontoons people go for these days, but a proper jetty, so old the oysters have over-colonised the pylons with their version of high-rise apartments. The boat is gone, though. It no longer hangs alongside the jetty, floating so high at high tide it is difficult to board, and so low at low tide it is almost, but not quite, on the bottom. It has been gone a good ten to fifteen years. It went before Mum died and so was the first loss of my childhood. I cried bitterly, tipped upside down in the sea locker reaching for the old lifejackets when we cleared it for sale. If I try only a little, I can smell it now, the diesel and the salt of us two weeks aboard at Christmas time and not looking to go home soon. I would sit on the roof above the wheelhouse as we steamed toward the bay filled with a sense of Huckleberry Finn adventure and I would sit in the same position on the way back wishing something would happen to prevent our return. I’d be brown as a berry and unused to proper clothes.

I have come this time for the outside table. I can’t seem to come for everything at once. The table is made from a large trunk of a tree and topped with a table top tiled by my mother. Need I say, Mum made Dad haul the tree trunk out of the river after it floated down in the ’74 flood? Probably not. We manoeuvre the table down around the side of the house and hoist it onto the truck. I’ll place it under a large tree in my paddock at home. I can see it there, not too far from the creek, which floods in its own right. It is a mirroring, of sorts.

I return through the house, straight through the hall, past the clock, through the big glass door, past the phantom plant and onto the verandah. I wonder how many more times I will do this. Not many more, I think. I will have to come back for the grandfather clock, I know. I stare at the bare earth on the lawn where the table stood and I wonder how does one leave a place like this? All I can say is its a process.